By Dr Richard M. Smith, Berkeley Mathematician and PhD in System Science.

It’s difficult to fathom how big tech has gotten as close as it has to global dominance over the past quarter century, yet here we are. Today, the five biggest tech companies constitute 22% of the market capitalization of the S&P 500. That’s right – 1% of the companies in the S&P 500 make up 22% of the total value of the S&P 500.

Regulators, moreover, are struggling to rein in big tech under existing antitrust law as evidenced by the recent decision by a Federal District Court to dismiss a major antitrust suit against Facebook brought by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) as well as a parallel suit brought by 48 state attorneys general. Facebook celebrated by soaring to join Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Google in the rarefied air of the $1 trillion dollar market cap club.

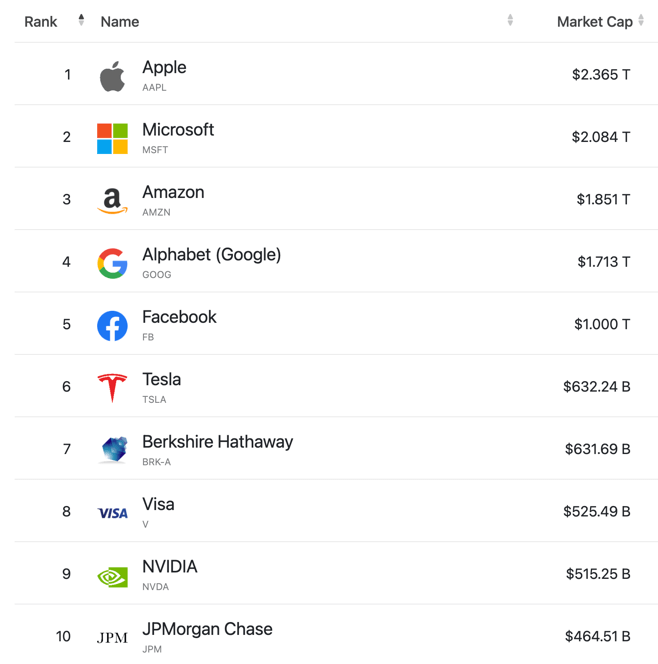

Just take a look at this shocking list from companiesmarketcap.com as of 7/6/2021:

These 5 tech titans are simply taking over the economy. Meanwhile, sixth on the list is Tesla (another aspiring tech titan) and seventh on the list is Berkshire Hathaway where 40% of the portfolio consists of Apple stock! It’s sobering indeed.

President Biden has taken a significant step in the right direction by appointing a new young gun to head the FTC – Lina Khan. Ms. Khan may turn out to be to big tech what Ida Tarbell was to big oil back a century ago – only Ms. Khan is armed with a J.D. from Yale Law School.

In her groundbreaking 100 page “Note” published in the Yale Law Journal back in 2017 she focused her sights on Amazon and had this to say about Amazon’s market dominance:

It is as if Bezos charted the company’s growth by first drawing a map of antitrust laws, and then devising routes to smoothly bypass them.

Ms. Khan is onto something here and her appointment to be the head of the FTC has put big tech on notice that this time may well be different. Big tech has indeed taken notice. Amazon even went so far as to ask that Ms. Khan be recused from overseeing Amazon given her “long track record of detailed pronouncements about Amazon, and her repeated proclamations that Amazon has violated the antitrust laws, a reasonable observer would conclude that she no longer can consider the company’s antitrust defenses with an open mind.”

Sorry Amazon, her “long track record of detailed pronouncements” is exactly why she was appointed to head the FTC.

For too long now, big tech has been playing with regulators much like someone with a laser can play with a kitten. Big tech dazzles and obfuscates and then hides under the pretense of “lowering prices for consumers” and “giving consumers the convenience they crave.” Meanwhile, the burden of proof is on the regulators to prove that things like predatory pricing (i.e., lowering prices to crush competition long enough to establish dominance) is harming consumers in ways seen and unseen. After all, what could be wrong with lower prices?

For the past 50 years now, antitrust law in the United States has centered around the notion of “consumer welfare” with the primary measurement of “consumer welfare” being measured by prices of goods and services. No one, at the time, imagined that a company like Amazon would come along and game the system by systematically leveraging predatory pricing for nearly two decades to establish dominance. Such is the genius of Bezos and company.

Finally, we have someone at the FTC that gets it. The so-called “consumer welfare” standard of current antitrust law is not up to the challenge of taking on the titans of tech. Ms. Khan correctly points out that the original foundation of U.S. antitrust law wasn’t just about pricing power – it was about process and structure and “excessive concentration of economic power.”

Authentic antitrust regulation is about more than just constantly lower prices. To quote Ms. Khan again it should promote “a variety of aims, including the preservation of open markets, the protection of producers and consumers from monopoly abuse and the dispersion of political and economic control.”

She goes on to say that focusing exclusively on consumer welfare, “disregards the host of other ways that excessive concentration can harm us – enabling firms to squeeze suppliers and producers, endangering systems stability (for instance, by allowing companies to become too big to fail), or undermining media diversity, to name a few.”

If you spend any time on the Internet, you know that avoiding Facebook, Amazon, Apple and Google is not easy. Almost every click puts money in their pockets, from ad views to purchases to video streams.

They are everywhere. And that’s not even what’s most alarming! It’s the amount of data that comes from each click. Just by living our lives in the 21st century, we surrender a huge amount of our privacy to a few immense corporations. Until recently, it was an unchallenged opinion that personal data should remain personal. Today, that seems like the distant past.

The “free” services that dominate the digital landscape have made privacy obsolete. Data is the most valuable commodity in the world right now, and we hand it over every day to the biggest tech companies, in exchange for basic services like email and search.

The oil and steel companies of old were considered monopolies because they were inescapable, stifling competition and providing no real alternative for the consumer. Is there any more apt equivalent today than the data-powered juggernauts now under fire?

If you find the tradeoff of data for convenience a fair exchange, realize that the next step — what’s actually done with our data — is almost completely hidden from us.

The result is a casino-like imbalance of power. The whole game is tipped in favor of the “house,” who write and rewrite the rules as they go. The algorithms that determine so much of how we live our lives are, quite literally, trying to think for us. The tech giants understand the rules (because they write them), and we don’t.

There are few things today in the United States that inspire bipartisan support at the Federal level. Big tech antitrust regulations and legislation is one of them. We should wish Chairwoman Khan all the best in her new role and we shouldn’t worry too much if a few eggs get broken in the overdue process of restoring true competition and innovation in the technology economy.